During this year, two significant people – Noël Treanor and Marc Lenders – in relations between the churches and the European Union have died.

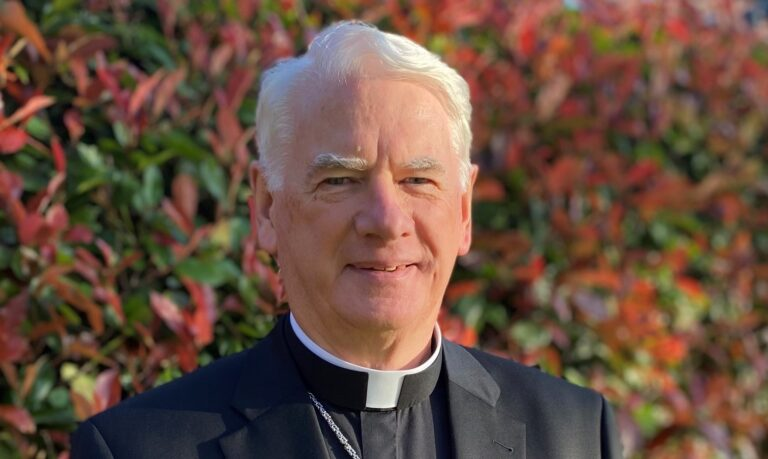

Image from the diocese of Down and Connor webpage

Archbishop Noel Treanor, who died suddenly on Sunday 11 August 2024, aged 73, was one of the foremost church representatives working alongside the European Union institutions in Brussels. He joined the staff of the Commission of Bishops’ Conferences in the European Union (COMECE) in 1989 and, in 1993, became its General Secretary. He served in that capacity until 2008 when he became Bishop of Down and Connor, returning to Brussels as Apostolic Nuncio to the European Union in 2023. Earlier he had been Prefect of Studies at the Pontifical Irish College in Rome and worked in several parochial and diocesan appointments in Ireland.

I worked closely with Noël when he was General Secretary of COMECE and I was General Secretary of the European Ecumenical Commission for Church and Society (EECCS). He was always open to ecumenical co-operation and readily joined the dialogue meetings with the European Commission which EECCS had started in the early 1990s. He also contributed much to the meetings with national governments when they held the rotating Presidency of the European Council, making it easier to arrange meetings with governments in predominantly Catholic member states.

Our closest collaboration was over the development of more structured relationships between the churches and the European Union which led eventually to Article 17 of the Lisbon Treaty which, for the first time, gave a legal basis for an open, transparent and regular dialogue between the EU institutions and churches, religious associations, and philosophical and non-confessional organisations.

Our co-operation also came into play when the European Commission proposed to extend European anti-discrimination legislation to cover, among other things, discrimination on the grounds of religion and belief. The original draft of the legislation would have made it difficult for churches to restrict appointments to their own members – a clash between the anti-discrimination principle and the right of freedom of religion and belief. Together, we were able to mobilise national church organisations, particularly in Germany, Ireland, Finland and the United Kingdom, to take up the issue with their governments, resulting in a positive outcome in the Council of Ministers.

In all his dealings, Noël was courteous, kind and diplomatic but he was equally capable of being firm. This was something I observed on numerous occasions but nowhere more so than when he and I spent much of a weekend negotiating with the President of the European Humanist Federation over the text of what I was to say when addressing the civil society hearing of the Convention on the Future of Europe on behalf of communities of faith and conviction.

Noël was a great communicator and did much both to make Catholic positions on European issues known to the EU institutions and explaining the EU to church people – something which he continued as Bishop of Down and Connor when he represented the Irish Bishops’ Conference in COMECE.

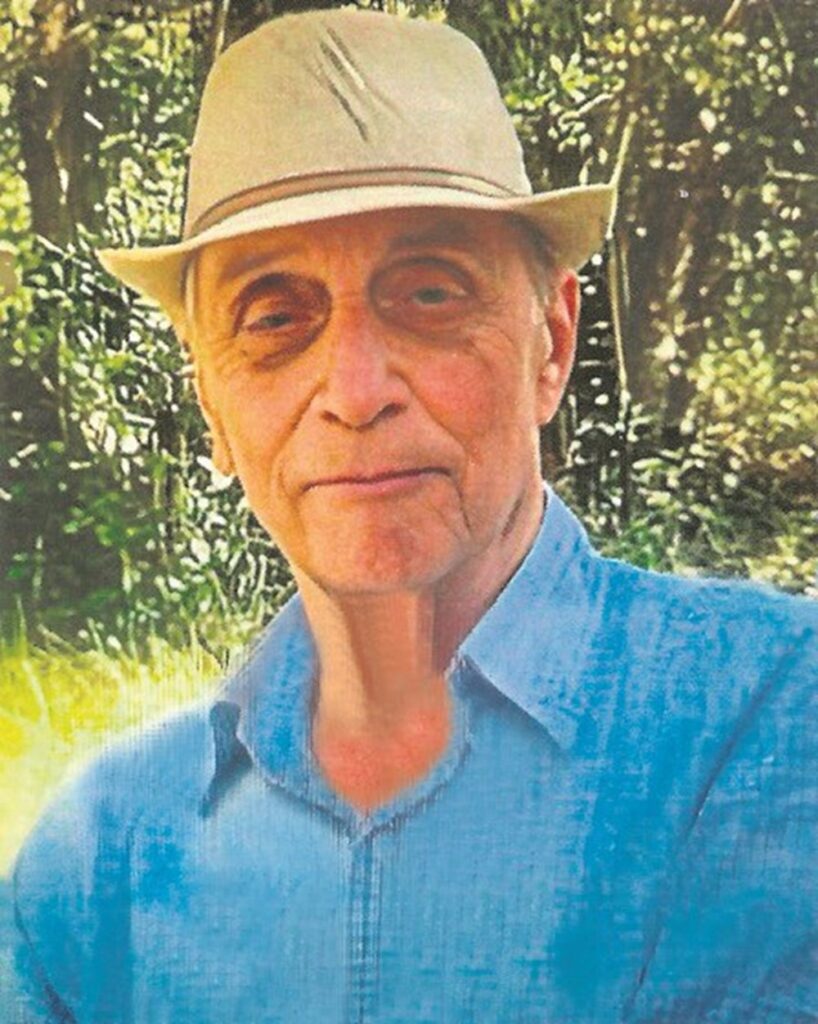

Revd. Marc Lenders, who died on 21 March 2024 aged 89, was a pastor of the Netherlands Reformed Church who pioneered the ecumenical presence at the heart of the European institutions.

The Ecumenical Association for Church and Society had been started by a group of European civil servants and local pastors in the 1960s, aimed at interesting the European Churches in the European project, as well as creating a network of mutual support. The Association decided to employ Marc as their Secretary – at first a part time appointment, combined with Marc teaching religion in the European Schools.

Gradually, the work increased and some of the Protestant and Anglican churches in European Community states (then only six) together with the United Kingdom, set up the body which was to become the European Ecumenical Commission for Church and Society. For years Marc worked in a minute staff team, rarely more than three, often only two. Nevertheless, he made a substantial impact in his and the Ecumenical Commission’s contacts with the institutions, including advocacy for the Common Agricultural Policy to have the quality of rural life as one of its pillars and support for non-governmental organisations working against apartheid in South Africa.

Marc was also involved in the organisation of the Roehampton Conference of 1974 which was instrumental in mobilising people in the British churches in favour of British membership of the European Communities in the subsequent referendum.

In the late 1980s, churches became more interested in Brussels and Strasbourg as European legislation broadened and potentially affected the interests and status of churches. Simultaneously, policy increasingly impinged on areas of church concerns – employment, poverty, social policy and development aid. Marc had played a major role in explaining the issues to the churches.

By 1989, for the first time, resources were available to increase the staff. I am very grateful to Marc for the warmth of his welcome when I arrived in Brussels and the generosity of spirit which enabled him to accept someone coming in to run the organisation which he had served for so long. As Study Secretary, he was glad to be freed of administrative tasks and to be able to concentrate on what he loved most – thinking, imagining, and developing vision – and sharing it with colleagues and the wider Church, something he did until his retirement in 1999 – and indeed afterwards.

Keith Jenkins 14/08/2024